MARCH 2024

Friday, March 1

Trois Crayons (French, "three crayons") The technique of drawing with black, white and red chalks (à trois crayons) on a paper of middle tone, for example mid-blue or buff. It was particularly popular in early and mid-18th century France with artists such as Antoine Watteau and François Boucher. (Clarke, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms)

Coming Up

Dear all,

Greetings from Trois Crayons HQ. Welcome to the March edition of the newsletter.

It’s a busy month ahead for the drawings world with the art fairs TEFAF, Maastricht (9 - 14 March, preview 7-8), and the Salon du Dessin, Paris (20 - 25 March), on the horizon. Galleries and dealerships from around the world will descend on the two cities for two and a half busy weeks. See our ‘Preview’ section below for a short interview with the Salon du Dessin’s President, Louis de Bayser, and a look ahead to the events taking place in the French capital, including the launch of our board game (21 March, 6 pm @ 346 Rue Saint-Honoré)! This month we’ve picked out 5 current and upcoming events from France and 5 more from around the world, spoken with Luca Baroni, director of the Rete Museale Marche Nord, about his favourite Barocci drawing, and chosen a selection of literary, visual and audio highlights. As ever, you can test your inner connoisseur with the real or fake section.

NEWS

In drawings news, The Paper Project, a Getty Foundation-funded initiative launched in 2018 to help graphic arts curators navigate the demands of the modern museum, has announced its final round of funding for a number of initiatives. The full list of grants is viewable here and a number of the events are already open to applicants. Don’t hang around, applications for the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin’s traveling seminar on the graphic work of Lucas Cranach the Elder will close on March 10th, and applications for ‘Touched/Retouched: Paper across Time (1400–1800)’ at the Bibliotheca Hertziana will close on March 20th. In Paris, the Fondation Custodia has announced the launch of a new version of their database dedicated to collectors’ marks on drawings and prints. In the UK, the Ashmolean will open a new exhibition this month featuring ‘Great Flemish Drawings’ from Antwerp and Oxford collections. In the US, The Tribune de l’Art recently broke the news that the Getty have acquired an impressive unpublished drawing by Baccio Bandinelli, and in other acquisition news, the Art Institute of Chicago has acquired a drawing by Jean Baptiste Debret after Jacques-Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii.

In the academic noticeboard, a number of funding opportunities have also been announced this month for writers focusing on drawings. The association Bella Maniera has launched Le Prix JRC, with submissions are due by the 2nd April. The Burlington Magazine has announced a scholarship for the study of French 18th-century fine and decorative art, with applications closing on the 17th March. Master Drawings has announced the 7th edition of the Ricciardi Prize with submissions due by the 15th November. A call for papers has also been issued for a conference on life drawing which will be hosted at the Courtauld this coming June. Applications are due by the 22nd March. In the coming weeks, conferences on 16th century drawing in Rome and on the practice of landscape drawing from 1500–1800 will take place in Venice and Rome respectively, the latter of which can be livestreamed. And finally, at the Morgan Library & Museum, applications are now open for the Moore Curatorial Fellowship in the Department of Drawings and Prints, with a deadline of March 24th.

For this month’s edition we have picked out 10 current events from across the France and around the world, previewed ‘Paris drawing week’, spoken with Luca Baroni, director of the Rete Museale Marche Nord, about his favourite drawing, continued our interview with Greg Rubinstein and recommended a selection of literary and audio highlights. As ever, you can test your inner connoisseur with our real or fake section.

Please direct any recommendations, feedback, event listings or news stories to tom@troiscrayons.art, they are all appreciated.

EVENTS

This month we have picked out 5 new and previously unhighlighted events from France and 5 from further afield. For a more complete overview of ongoing exhibitions and talks, please visit our new Events page.

FRANCE

Wordlwide

Preview

Paris Drawing Week and the salon du dessin (20th - 25th March)

The Salon du Dessin is the world’s premier art fair dedicated to the collection, study and exhibition of drawings, from the Renaissance to the present day. Hosted at the Palais Brongniart in Paris the event extends beyond the confines of the old Stock Exchange and since its creation in 1991 has initiated a veritable “Drawing Week” towards the end of March each year, with museum collaborations, pop-up exhibitions, a symposium, visits to collections and a contemporary drawing prize all taking place in the same week.

This year’s two-day symposium, under the direction of Marco Simone Bolzoni, curator of Old Master and 19th century drawings from the Debra and Leon Black collection, New York, will be devoted to the theme of "Travel drawings". Running from the 20th to the 21st March, the timetable of talks is viewable here.

Five Quick Questions with Louis de Bayser, Président du Salon du Dessin

1). Le Salon du Dessin

In the publication released in 2016 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Salon du Dessin one Parisian curator described the Salon du Dessin as the ‘Fashion Week’ of the drawing world. How would you describe the Salon du Dessin to a newcomer and what should they expect to discover inside the colonnades of the Palais Brongniart this year?

The Salon du Dessin is a specialty show. It allows for 39 dealers to exhibit their latest finds all under one roof, the Palais Brongniart. This gives collectors – and newcomers - the chance see drawing in all its diversity: from portraits to landscapes, by way of religious or mythological scenes, from the 16th century to the present day, from charcoal to watercolour, from pastel to red chalk.

2). La Semaine du Dessin

Partnerships with museums and academic institutions are clearly an important element of the Salon du Dessin’s programming, which now runs its own free on-site symposium, organises visits to special collections, and coincides with the launch of a number of museum exhibitions. Is there one talk in particular from this year’s programming whose subject matter has piqued your interest, and is there a collection visit that you are particularly excited to have facilitated?

The topic of this year’s symposium is “Travel Drawings”. The programming is directed by Marco Simone Bolzoni who has organized the various conferences for the next two editions of the fair. This year the symposium deals with journeys made by artists during the 16th and 17th centuries. One of the talks I'm most excited about is that of Dr. Christoph Metzger who will be speaking on Dürer's famous trip to Italy: “Next Stop Vienna: With Dürer on the Road to Venice”.

3). The Venue

It’s exactly 20 years since the Salon du Dessin moved home to the Palais Brongniart in the 2nd arrondissement. What makes this venue so special, and do you envisage the fair ever expanding beyond the 39 exhibitors that it hosts today?

When the Salon du Dessin moved to the Palais Brongniart in 2004, the venue was almost too big for the fair at the time. But the growth of the Salon du Dessin under the presidency of Hervé Aaron in the subsequent years allowed for the Salon to make the most of this magnificent Palace. The Salon du Dessin fits very well there and, for the moment, we have no intention of moving on.

4). Les Invités d’Honneur: The Fondation Dubuffet

Each year a museum or public institution is invited to present a selection of their drawings at the Salon. Can you tell us about this year’s guest of honour, the Fondation Dubuffet?

Each year we invite a different institution to exhibit at the Salon du Dessin. This year we will have a monographic exhibition since it is the Dubuffet Foundation who will be showing a group of approximately 40 drawings retracing the graphic evolution of Dubuffet over the years.

5). Highlights

As ever, you yourself will be exhibiting with your family-run gallery, Galerie de Bayser. Is there a work that you are particularly excited to share with visitors, and is there a work from another exhibitor that you are particularly excited to see for yourself?

Like every year, we will be exhibiting a set of drawings ranging from the 16th to the 20th centuries at the Salon. This year we will be presenting a set of Flemish drawings around Hans Bol. At the same time, we will be showing a group of French drawings from the 19th century, including a magnificent figure study by Ingres and a very lively study of wild beasts by Delacroix.

Pop-Up Exhibitions Beyond the Palais Brongniart

Vacant galleries also present younger dealers with the opportunity to host pop-up exhibitions in these spaces whilst their proprietors are exhibiting nearby at the Salon.

Galerie la Nouvelle Athènes @ 22 Rue Chaptal (7 Mar - 29 Mar)

Galerie Lowet de Wotrenge and Poncelin de Raucourt Fine Arts @ Galerie Alexis Bordes, 4 Rue de la Paix (18 Mar - 25 Mar)

Den Otter Fine Art @ Benjamin Perronet Fine Art, 10 Rue de Louvois (19 Mar - 25 Mar)

Sabrier & Paunet @ Galerie Ambroise Duchemin, 51 Rue Saint-Anne (19 Mar - 26 Mar)

Annual Reception @ Nicolas Schwed, 346 Rue Saint-Honoré (20 Mar, 6 pm - 9 pm)

Trois Crayons Old Master Drawings Board Game Launch Party @ Nicolas Schwed, 346 Rue Saint-Honoré (21 Mar, 6 pm - 9 pm)

Drawing of the Month

FEDERICO BAROCCI (C. 1533-1612)

Virile torso with a reclining head (a study for the Perugia’s Deposition), 1568-69

Black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on blue paper, with spots of vermilion, salmon, and ochre oil paint, 212 x 227 mm, Private Collection

Luca Baroni, director of the Rete Museale Marche Nord and author of federico Barocci’s catalogue raisonné (forthcoming, summer 2024), has kindly chosen our sixth drawing of the month

When Covid-19 arrived in early 2020, I was stuck in London for three months. At that time, I was preparing my doctoral thesis concerning the new catalogue raisonné of the Urbino artist Federico Barocci (c. 1533-1612). It was during those strange weeks, being confined at home, that a private collector sent me the drawing reproduced here. He kindly left me the original "to keep me company" and as an incentive to continue my research despite the difficult circumstances.

My quarantine companion, a sketch of a male torso with a bowed head in black and white chalk on blue paper, can be connected to the altarpiece of the Deposition, painted by Barocci for the Cathedral of Perugia in 1568-69. Until recently, the drawing was hidden on the back of a pastel head study for the same composition and has therefore retained much of its freshness. The sheet is evidently a short note, later reused by the artist to give life to the drawing on the recto and probably not destined to survive. Precisely for this reason, however, it allows us to intimately penetrate the artist's creative daily life. The multi-coloured paint stains (which always reminded me of the fake blood stains left by the Canterville Ghost in his fight against the Paragon detergent) evoke the permanence of the sheet on the worktable, and it is somehow moving to be still able to identify today the same colours (pink, red, orange) on the finished canvas.

When I first saw the drawing, my immediate thought was "If there wasn't an artist called Barocci, this drawing would probably be called a Titian." The impression does not derive only from the medium and the subject chosen, similar to Titian's sketch of a Deposition in the Uffizi: but from the extraordinary strength with which Barocci shapes the naked virile figure of Christ, a proportionate and beautiful body captured in the moment in which life fades. As subsequently emerged during the research, the link between Barocci and Titian is not entirely casual. Not only were the Venetian artist's paintings and drawings widely visible and admired in Urbino; but when the altarpiece of the Deposition was first shown to the public, on 24 December 1569, a contemporary commentator, Raffaele Sotii, declared that "It is believed that that work should be held by experts of the highest value, because Messer Federigo is a great imitator of Tiziano Vecello and because it shows a reality truly new, artificial, full of grace and goodness in every part". If the painting does not immediately recall Titian, the sketch certainly does: a further proof of the incredible importance of drawing in Barocci's work, as a key to penetrate his inexhaustible creative soul.

Luca will be giving a talk at the Salon du Dessin’s international symposium on Thursday 21st March: “A Star that Bewitches People: The Georgian Drawings of Father Cristoforo Castelli (1632-1654)”

DEMYSTIFYING DRAWINGS

How To: know when an attribution is ‘right’

Greg Rubinstein, Senior Director and Head of the Old Master Drawings Department at Sotheby’s, discusses the complex issue of authorship.

PART 2

To what extent have new technologies impacted your work and what changes do you foresee in the near or distant future?

Access both to new analytical technologies and to databases of information relating, for example, to watermarks and paper structure, are both immensely beneficial. When my colleague Cristiana Romalli was researching the extraordinary Mantegna modello for one of the great Hampton Court tempera paintings of The Triumphs of Caesar, in preparation for our sale of the drawing in New York in January 2020, it was infrared photography – something that has not been used all that much in the study of drawings – that revealed the fundamental compositional change to the left of the drawing, which proved beyond any doubt that this was indeed a working design by Mantegna himself (the only one for the series that survives).

As for future developments, there has been much talk of AI’s potential for recognising patterns of mark-making, and thereby making attributions, but I have to say the examples that I have seen so far don’t inspire much confidence or excitement. At this point, at least, the analysis will only ever be as good as the instructions and the dataset of examples that are provided to the system, and I see no evidence that we yet have a sufficiently sophisticated and nuanced way of doing this to yield valid and interesting results.

Step 1A: Evidence.

Gather all physical evidence: watermarks, inscriptions, collection marks, signatures, mount, condition and so on.

Step 1B: Evidence.

Gather all documentary evidence: given provenance, sale history, publications, reproductions and so on.

Step 2: ANALYSIS.

Is the paper type consistent with the drawing’s style? Are the artist’s materials consistent with the period and location? How reliable is the inscription? If the drawing is published, how reliable is the publication? What is the function of the drawing?

Step 3: CONCLUSIONS.

A combination of the empirical and the subjective. What ‘circle of possibility’ does the evidence indicate? Does instinct match evidence?

I do, though, have higher hopes for non-invasive optical and microscopic analysis, right down to a molecular level, of pigments used, which, when used in conjunction with substantial databases, may permit us to detect fascinating patterns. If, for example, we could establish that the ink in certain drawings by a particular artist has precisely the same physical or chemical structure, that would strongly indicate that those drawings were made at the same moment.

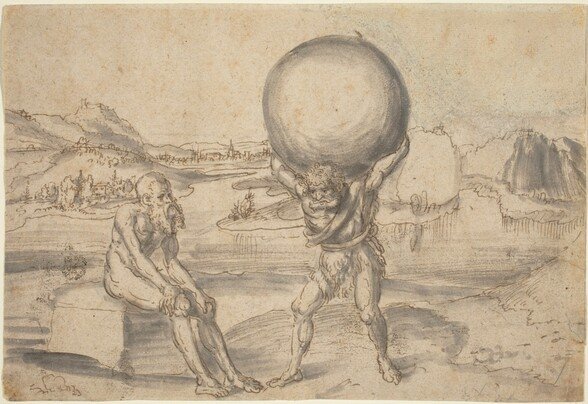

Is there an anonymous drawing that has passed through your hands that still irks, either because it has since been identified, or because it has remained tantalisingly elusive?

That’s a difficult (and slightly painful) question to answer! Though given that during my time at Sotheby’s we’ve probably had at least 30,000 drawings pass through our hands, many of them arriving with little or no background information and researched by us in a very short time, it’s unavoidable that one or two will have escaped our collective beady eyes, and slipped through the net. Of those that I know about (which I hope includes all the significant ones…), one that I think of with some annoyance is the drawing of Atlas and Hercules by Lucas Cranach, now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, which we offered for sale in New York in 1997, as ‘German School, 16th Century’. I can at least partially forgive myself for not having known immediately, from the poor black & white photo that was all we saw before getting to New York a few days before the sale, that it was a rare and somewhat unusual Cranach drawing, but when half the leading curators and collectors in the world spent much of the viewing hovering around it like flies, the alarm bells should have been louder, and I really should have done what was necessary to work out what it was! In the event, the drawing made its price ($277,500, against a pre-sale estimate of $4,000-6,000 – much the same, I believe, as it would have made if it had been correctly catalogued), which was a great relief. But still…

As for the other half of the question, yes, there are quite a few wonderful drawings that I’ve known for many years, but that still prove stubbornly resistant to attribution. My colleagues and I often say to each other “it’s so good, we have to be able to work out who did it!”, but sadly that’s not always possible. What is true is that as the level of quality increases, the chances that a drawing was made by someone we’ve never heard of correspondingly decrease. But at the same time it’s important to remember that the very erratic survival of drawings over the centuries means that for some artists we have many drawings, while for others we have none at all, even though the records of their estates mention hundreds and hundreds of drawings, all presumably now lost, meaning that we have absolutely no idea of that artist’s drawing style. Maybe the mystery high-quality drawings are lone escapees from the fate suffered by their maker’s other drawings.

Is there an authorship that you are particularly proud to have recognised?

I think the most satisfying attributions are often those that come most instinctively and take the least time, but the context in which the attribution is made also plays a big part in how one remembers it. One particularly happy memory for me is spending an afternoon in 1994 going through – at breakneck speed – box after box of drawings at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, with David Scrase, who was preparing an exhibition of Dutch highlights to send to various German museums. One rather lovely farm landscape there had gone under several different names, but it seemed to me very clear it was by Cornelis Saftleven, and it duly went into David’s exhibition with this new attribution. There was also a drawing in Egbert Haverkamp Begemann’s own collection which he thought was by John Michael Rysbrack, but I recognised as a late work by Jacob de Wit.

It’s also satisfying to come up with something interesting outside one’s main area of expertise. Two years ago, we were looking at what we believed to be a slightly eccentric Italian drawing, struggling to find a convincing attribution, when I suddenly had the idea, for no reason that I can really explain, that we might actually be looking at an El Greco. There are hardly any certain El Greco drawings to compare with, so we conservatively described it as ‘Circle of El Greco’ when we offered it for sale, but in the event the attribution was accepted by several leading Spanish drawings scholars, and the drawing was acquired, as an El Greco, by the New York Hispanic Society.

Real or Fake

Can we fool you? The term “fake” may be slightly sensationalist when it comes to old drawings. Copying originals and prints has long formed a key part of an artist’s education and with the passing of time the distinction between the two can be innocently mistaken.

Can you discern the real from the fake? For this month’s bonus points, name the artist and the sitter. A clue: they’re related.

Scroll to the end of the newsletter for answers.

Resources and Recommendations

to listen

The Black Art Visionary Who Secretly Built the Morgan Library

The hidden story of Belle da Costa Greene (1879 - 1950) is a wild one. A brilliant scholar and authority on illuminated manuscripts, da Costa Greene was responsible for building John Pierpoint Morgan’s peerless collection, which includes drawings by Leonardo, three Gutenberg Bibles and original scores by Mozart. What is less well known is the fact that da Costa Greene was Black, and passed as white for her entire adult life, guarding the secret.

Listen on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

to watch

The Raphael Cartoons: Making the tapestries | V&A

Another informative process video this month, this time coming from the V&A and providing an overview of the three-year process that led to the creation of Raphael’s famous tapestries for the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Palace.

to read

Drawn to greatness – the personal collection of Katrin Bellinger

In 2022 Susan Moore, art market correspondent and associate editor of Apollo, sat down with the dealer-turned-collector, Katrin Bellinger to discuss her personal collection, and the reasons behind its thematic focus: depictions of the artist at work.

answer

The original, of course, is on the right (lower image on mobile). The drawing is by Moses ter Borch and the sitter is the artist’s father, the artist Gerard ter Borch the Elder.

On the left (upper image on mobile): Manner/Style of: Gerard Ter Borch II, Head of a bearded old man wearing a large hat; slightly to right, British Museum, London, inv. no.: 1992,1003.178.

On the right (lower image on mobile): Moses ter Borch, Portret van Gerard ter Borch de Oude, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. no.: RP-T-1887-A-1042.