May 2024

Wednesday, May 1

Trois Crayons (French, "three crayons") The technique of drawing with black, white and red chalks (à trois crayons) on a paper of middle tone, for example mid-blue or buff. It was particularly popular in early and mid-18th century France with artists such as Antoine Watteau and François Boucher. (Clarke, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms)

Coming Up

Dear all,

Greetings from Trois Crayons HQ, where we have been busy posting out the first orders of Attribution! and making arrangements for our installation at No.9 Cork Street this summer during London Art Week (28 Jun – 5 Jul). More information on this will be released shortly, but for now, please mark your calendars.

For this month’s edition of the newsletter, we have picked out 10 current events from across the UK and around the world, spoken with Austėja Mackelaitė about her favourite drawing in the Rijksmuseum, discussed ‘Bruegel to Rubens: Great Flemish Drawings’ at the Ashmolean Museum with the exhibition’s curator, An van Camp, continued our interview on collectors’ marks with Rhea Sylvia Blok of the Fondation Custodia, and recommended a selection of literary and audio highlights. As ever, you can test your inner connoisseur with the real or fake section.

Please direct any recommendations, feedback, event listings or news stories to tom@troiscrayons.art, they are all appreciated.

NEWS

In the UK, ‘Michelangelo: the last decades’ opens tomorrow at the British Museum. This opening follows the Casa Buonarroti’s digital publication of the first batch of Michelangelo drawings in its possession and last month’s sale of a Michelangelo ‘drawing’ at Christie’s, New York. The drawing in question, a scrap of paper with a diagram of a rectangular block of marble on it, was estimated at a cool $6,000 - $8,000 and sold for $201,600. Tickets to the exhibition are priced at a more reasonable £18. Down the road at Guy Peppiatt Fine Art in Mason’s Yard, an exhibition on the drawings of John Ruskin remains on view until Friday. Some good news – if not explicitly drawings related – has come out of Romania, where one of the three paintings stolen from the Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford, during the Covid-enforced lockdown has been discovered and returned to the museum.

In Berlin, a special exhibition on Maarten van Heemskerck’s Roman drawings has just opened, where the Kupferstichkabinett’s unrivalled collection of around 170 drawings will on view in its entirety for the first time, marking 450 years since the artist’s death. In Paris, the Fondation Custodia has recently opened an exhibition celebrating twelve years of acquisitions by the late director Ger Luijten. The Parisian institution has also announced the recent acquisition of a drawing by Hendrick Goltzius.

In further acquisition news, the Château de Versailles has announced the arrival of a drawing by Simon Vouet, exhibited by Nicolas Schwed during the Semaine du Dessin. La Tribune de l’Art has also reported on a number of museum acquisitions this past month, including a Laurent Guyot for the Mobilier National, a Eugène Lami for the Musée Condé, and a Boilly for the Musée de l’Armée.

In the United States, two curatorial positions have recently been advertised, one at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, for the position of Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings, and the other at The Clark, Williamstown, for the position of Curatorial Assistant for Works on Paper. Another role currently being advertised is at Christie’s, New York, where the auction house is in search of a new Head of Department. Act fast as applications close today. In conference news, registration for the Historians of Netherlandish Art 2024 conference, which will take place between London and Cambridge from 10-13 July, is now open and available here. Another relevant conference entitled ‘Papierkunst voor het publiek’ will take place at the Teylers Museum, Haarlem, on June 7.

EVENTS

This month we have picked out a selection of new and previously unhighlighted events from the UK and from further afield. For a more complete overview of ongoing exhibitions and talks, please visit our Events page.

UK

Wordlwide

DRAWING OF THE MONTH

Herman van Swanevelt (ca. 1603–1655)

Porta Pinciana in Rome, ca. 1629–41

Brush and brown ink over traces of black chalk or graphite, 206 x 272 mm Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. RP-T-1902-A-4593

Austėja Mackelaitė, Curator of drawings at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, has kindly chosen our eighth drawing of the month.

Among the eighteen gates that once punctuated Rome’s Aurelian Walls—the still partially extant system of fortifications, begun in the third century AD—the Porta Pinciana was neither the grandest nor the most important. Yet, for Herman van Swanevelt, the peripatetic Dutchman who had spent over a decade living and working in the Eternal City in the middle years of the seventeenth century, its picturesque potential seems to have been the only thing that mattered.

In the Rijksmuseum drawing, Van Swanevelt approached the Porta Pinciana from the northern end of what today is the glitzy Via Venetto. After outlining the gate’s complex architecture using chalk or graphite, he executed the rest of the sheet entirely in brush. With this single ordinary tool, Van Swanevelt produced the full gamut of strokes and marks, rendering the gate and its environs—from the delicate cracks in the facade to the messy foliage, which partially obstructs and threatens to overtake the building—with confidence and speed.

The drawing’s main protagonist, however, is light. The artist used the reserve of the paper to convey the impression of intense Italian sunshine hitting the crumbling walls of the ancient structure. Pools of brown wash—delicately transparent in some areas, dark and impenetrable in others—further enhance the feeling of overwhelming radiance. Like the Dutch Italianate artists who sojourned in Rome shortly before him—namely, Cornelis van Poelenburch and Bartholomeus Breenbergh—Van Swanevelt was more concerned with atmosphere than precision. Although it is unclear whether Van Swanevelt knew the two men personally, it is impossible to look at his bold, nearly abstract experiments with washes without imagining that he had direct access to their drawings and closely studied their approach to the Roman landscape.

While this fully resolved study could have easily found a Roman buyer, the sheet seems to have stayed in the artist’s hands, forming a part of his visual archive. Upon leaving Rome and settling in Paris in 1641, he returned to the composition and used it as the basis for an etching. For the next fifteen years, until his death in 1655, the decade he spent in Rome, captured in drawings such as this, remained the fixed axis around which his career as a draughtsman, printmaker, and painter rotated.

REVIEW

Bruegel to Rubens: Great Flemish Drawings (23 Mar – 23 Jun)

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Workshop of Tomasso di Andrea Vincidor (1493–1536), Fragment of a Tapestry Cartoon: Bust of a Woman in Profile, Christ Church, Oxford

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1526–69)The Temptation of St Anthony, c. 1556, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

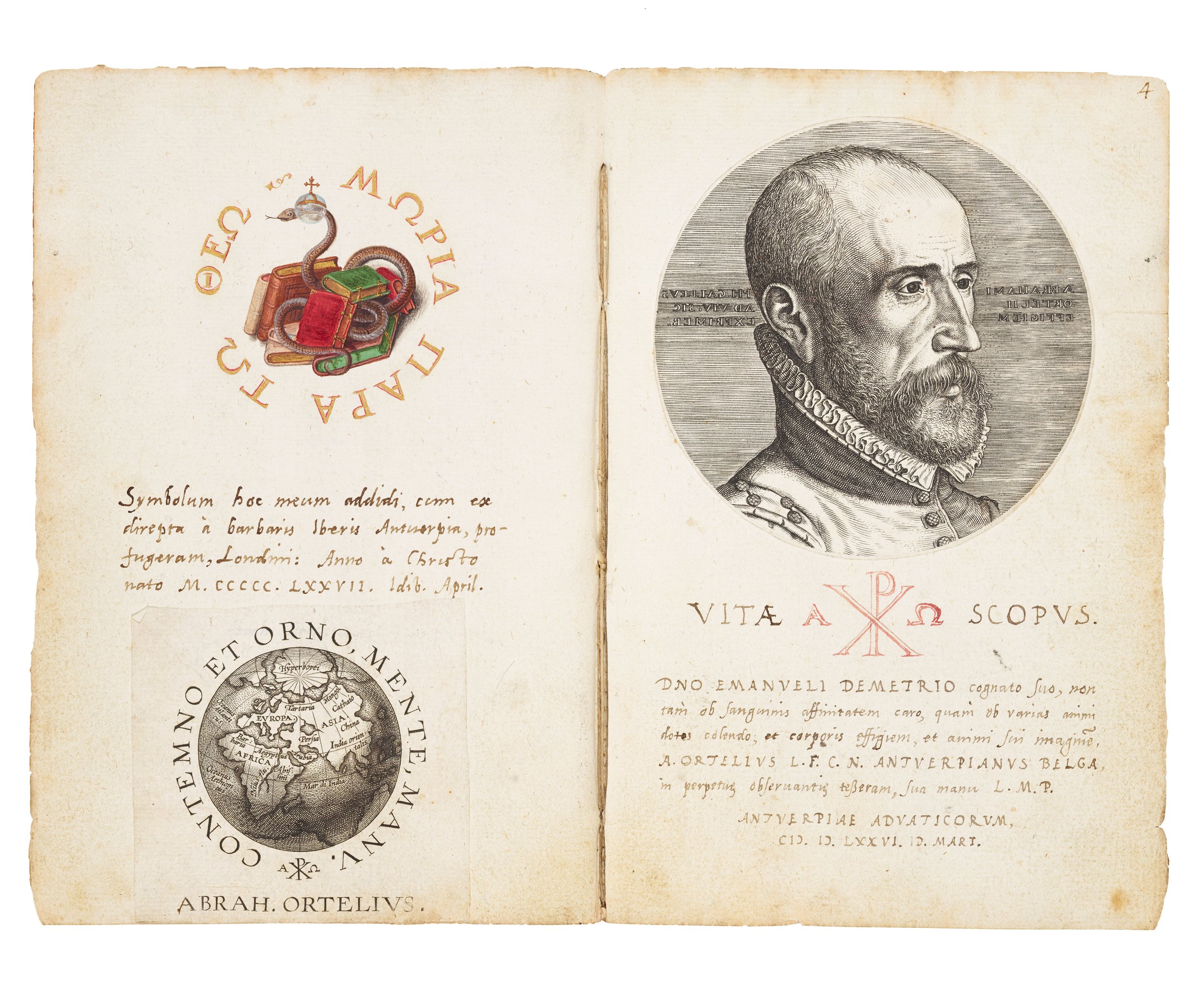

Album Amicorum of Emanuel van Meteren, 1576 & 1577, Friendship Contribution by Abraham Ortelius, folios 3v–4r, The Bodleian Libraries, Oxford

An interview with An Van Camp, curator of the exhibition and Christopher Brown Assistant Keeper of Northern European Art, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the timespan covered by the exhibition, Flanders, historically located in the Southern Netherlands and today a region of Belgium, was Catholic and governed by the Habsburg rulers of Spain. Drawings such as Pieter Bruegel’s raucous ‘The Temptation of St Anthony’ quickly dispel any misconceptions of sober Catholic orthodoxy in the region’s artwork, however. The drawings on display here are not bound by the urban centres of religion in which many of them were produced. They reveal the breadth of drawing’s potential functions, as well as representing both intimate local observations and a newfound worldliness, as the region opened up to trade and voyage, whilst the artists themselves looked south to Italy.

Could you outline the scope of the exhibition, some of the artists and works on display, and, perhaps most importantly, explain why visitors should make the trip to Oxford?

Bruegel to Rubens features almost 120 drawings, which were created by artists either working in or born in the Southern Netherlands during the 16th and 17th centuries. The exhibition stems from a partnership with the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp, who staged a reduced version of the show between November 2023 and February 2024. For the second venue at the Ashmolean Museum, we have chosen around 50 of the most exquisite drawings from Antwerp public and private collections, supplemented with Oxford’s finest sheets. The majority was naturally selected from the Ashmolean Museum, with additional loans from Christ Church college and the Bodleian Libraries. Over a quarter of the drawings are by Antwerp’s best-known Baroque son, Peter Paul Rubens, expanded with works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hans Bol, Joris Hoefnagel, Jan van der Straet (Stradanus or Stradano), Maerten de Vos, Anthony van Dyck, Jacques Jordaens, Abraham van Diepenbeeck, Jan Boeckhorst etc. The exhibition focuses on how these drawings were used in artistic practice at the time, with the three galleries covering the three main functions of South Netherlandish drawings: sketches of the world around them, including copies of other artworks and studies from life and nature; designs for other artworks, such as paintings, prints, stained glass, metalwork, tapestries, sculpture, temporary decorations and architecture; and finally, independent drawings made in their own right. Many of the Antwerp drawings are listed on the Topstukkenlijst (designated “Masterpieces” by the Flemish Government) and, because of their fragility and sensitivity to light, are not allowed to be shown again for the next ten years or so. In addition to Oxford drawings, many of which have never been displayed or published before, Bruegel to Rubens is truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see so many superb South Netherlandish drawings together. Bruegel to Rubens is still on until 23 June.

What message do you hope to convey through your curation of the exhibition?

I wanted to curate an exhibition in which the drawings were presented to the visitors in the most accessible way. The general public often still considers “old master” drawings as only understood by a select number of connoisseurs and specialists. However, by revealing how and why the artworks were made, we decided not to focus on their iconography or attribution, but rather highlight their function and related drawing techniques. These 16th- and 17th-century sheets were used as training and workshop materials, in addition to having been created as stand-alone artworks. The first room, dedicated to Sketches and Copies, introduces the various materials and techniques on the introductory wall and in a showcase. We even recreated Rubens’s drawing desk in a large display case through a variety of Ashmolean objects (Roman coins and intaglios, antique sculptures, Renaissance bronzes and plaquettes, Antwerp printed books), which feature in Rubens’s drawings (which are represented through facsimiles), in addition to drawing materials such as a quill, an inkpot and sheets of paper. It has been highly satisfying to see not only the visitors’ reactions but also to hear from other drawings specialists how effectively this one display brings the subject to life. The exhibition has succeeded in making visitors understand that these precious and fragile artworks were not always regarded as high-value artworks in collections, now professionally mounted and framed, but instead that they served a variety of practical functions at their time of creation.

Does the exhibition offer any new interpretations of the objects displayed, and were there any surprising discoveries made during the research process?

Because of the Antwerp-Oxford partnership, Bruegel to Rubens has managed to unite a unique collection of drawings which have never been shown together before. Over 30 drawings are in fact on display for the very first time and have only been recently (re)discovered and published. It was also possible to juxtapose related works kept in the various museum collections, such as for instance two designs by Jan Boeckhorst for the same tapestry and a Rubens title-page design shown with the copperplate made after it and the final printed version. We also united for the very first time six life-size tapestry cartoon fragments for the Vatican tapestry showing The Presentation in the Temple. In preparation for the exhibition, the Ashmolean was able to acquire an early impression of Pieter Bruegel’s The Temptation of St Anthony, of which we own the drawn design: one of the best-loved drawings in our collection.

The accompanying catalogue is intended to be consulted beyond the exhibition and to act as a manual to South Netherlandish drawings. The three main essays deal with the three major functions of drawings, as discussed above, and include one feature each focusing on sub-themes running through the exhibition: the internationality of the artists, their professional collaborations, but also their personal friendships and networks. Two introductory essays explain what a drawing is on a material-technical but also conceptual level, as well as provide a historical/geographical/cultural context of the Southern Netherlands.

As Vincent van Gogh wrote, drawing “is the root of everything”. Could you expand upon the relationship between drawings and the artworks produced in other media which are highlighted throughout the exhibition.

For centuries drawing has been described as the “Father of all the Arts” or the “Gateway to all the Arts” (Vasari and Karel van Mander). In Bruegel to Rubens this becomes all the more apparent. In the first gallery, Copying and Sketching, the different sub-sections reveal how artists started their artistic training by making copies and sketches of everything around them. It was less daunting to start copying from existing prints, such as Rubens’s album with copies after Hans Holbein II’s Dance of Death woodcuts. Budding artists then moved onto copying drawings, paintings, and eventually, three-dimensional objects such as sculptures. Once proficient, draughtspeople would venture beyond the study and make studies from nature, often en plein air, to finally attempt to make studies from life, such as portraits, ‘tronies’, snapshots of their pet animals and even an earthworm. But not only pupils would practice drawing and many artists continued to draw in order to create similar studies, but also designs for other artworks and independent sheets. No matter which specialism the artist would end up with, whether painting, printmaking, sculpture, architecture, decorative arts (metalwork, stained glass, and tapestries), drawings would usually lie at the base of any artwork created. This is illustrated in the second gallery devoted to design drawings, featuring both compositional studies, as well as detail studies, life-size designs or smaller compositions than the final artwork.

The Netherlands was in a state of flux during this period. How are the external influences of war, travel, trade, and colonial expansion reflected - or ignored - in some of these drawings?

Many of the drawings in the exhibition reveal the political and religious context against which they were created. The Southern Netherlands were not an independent region, but were under Spanish rule through local governors. Catholicism was imposed and this caused numerous rebellions, followed by religious persecutions. A set of designs for metal plaquettes by Maerten de Vos illustrate several historical events of the short-lived Liberation of Antwerp in 1577 from the Catholic Spanish. Two drawings are designs for temporary decorations (now lost but documented through these sheets) erected during Joyous Entries, when the Spanish governors established their rule. Some of the artists featured in the exhibition were Protestant and were either exiled or fled to more tolerant regions such as the Dutch Republic or the Holy Roman Empire. Some of the most stunning cabinet miniatures in the exhibition were possibly made for the courts in Munich and Prague, such as for instance Joris Hoefnagel’s Arrangement of Flowers. Most Netherlandish artists travelled within Europe as part of their training, with Italy being the top destination in order to learn from antiquity and Italian painters. Almost ten percent of the drawings on display were made in Italy, featuring copies of antique sculptures and gems, as well as Roman ruins, but also works by artist who permanently settled in Italy but kept proudly referring to themselves in their signatures as “Flemish”, such as Jan van der Straet (Giovanni Stradano) and Denys Calvaert (Dionisio Fiammingo).

Do you have a favourite drawing in the exhibition, or a favourite story that has come out of it?

When I was preparing the object selection for the exhibition, I came across a relatively unknown artwork, now kept at the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford. It is the friendship book or album amicorum belonging to the Antwerp historian Emanuel van Meteren. These albums have for many centuries been a widely popular socio-cultural phenomenon in large parts of Europe, including the Southern Netherlands. Surprisingly, British audiences are not familiar with the concept or holding a friendship album and requesting friends, family members, teachers, and colleagues to make contributions in them. These are usually kept for life and treasured as a reminder for long-lost or everlasting friendships. Emanuel van Meteren wrote a history of the Netherlands and was moreover a nephew of the foremost Antwerp cartographer Abraham Ortelius. His album is filled with numerous contributions by his peers, including his uncle’s but also masterpieces by contemporary artists and humanists such as Joris Hoefnagel, Lucas d’Heere, Philips Galle, Hubert Goltzius, Justus Lipsius etc. The pages opened in the exhibition contain two contributions by Abraham Ortelius: one created in 1576 with a portrait print and his motto, followed up by a second contributed added a year later after the Spanish Inquisition had confiscated Van Meteren’s album in order to identify his Protestant network. Ortelius skilfully, but daringly, drew an allegory of the Spanish king Philip II as a serpent coiled around a pile of books.

DEMYSTIFYING DRAWINGS

How To: UNDERSTAND A COLLECTOR’S MARK

To mark the recent launch of the new Marques de Collections website, our editor speaks with Rhea Sylvia Blok, conservateur at the Fondation Custodia, Paris, about collectors’ marks, their history and the changes to the database.

Marques de Collection

Collectors’ marks are integral to the understanding of a drawing’s history, but they are little known or understood outside of the sphere of drawings enthusiasts. As remarked upon at a recent event at Master Drawings New York, drawings people are bonded by a mutual understanding of subject-specific terms like ‘Lugt number’ and ‘counterproof’ and are liable to spend much of their time discussing things like ‘hands’. Thanks to Marques de Collection however, collectors’ marks need not be the domain of the specialist and can be easily understood with the aid of this invaluable tool.

Interview Part 2

Do you encourage members of the public, from dealers to collectors and researchers, to get in contact if they come across a mark which is hard to identify or unknown?

Establishing a reference work of collectors’ marks requires the support of the international community of drawing and print specialists. It is thanks to members of the public contacting us that our small team was able to constitute an important documentation of all kind of marks. We would also like to point out, that we encourage everybody to contact us with questions about collectors’ marks, especially marks that are not yet in the database. Often, we do have a file on these marks, especially if they are not published yet. We are always happy to provide information to those who contact us!

Step 1: Examine the front (recto) and back (verso) of the drawing as well as the supporting mount.

Marks may be subtly placed in a dense corner of the drawing, or on a more obvious blank area of a supporting mount.

Step 2: Assess the marks, stamps and inscriptions.

Look at the text (initials, words, numbers etc), image (animal, geometric shape etc), technique (handwritten, stamped etc), colour etc.

Step 3: Input information and search the database.

Enter as much information as possible into the search engine and explore the results.

Step 4: Results.

If no result corresponds to the mark you are looking for you can enlarge your search by deleting a query. For example, ‘colour’, as not all possible colours may have been indexed, or an initial that might not be clear. If the mark you are looking for is still not part of the results, do not hesitate to contact the Fondation Custodia collectors’ marks team at: marques@fondationcustodia.fr

Drawings enthusiasts, dealers and collectors are often, by necessity and wont, collectors of books too. Are there plans to publish a third physical edition of Les marques de collections de dessins & d’estampes?

Having found many more new marks than expected the idea to bring out a paper edition would result in a publication consisting of an estimated bulky six volumes, including the updated volumes of 1921 and 1956. A book edition would also raise the following problems: first of all, the difficulty of establishing an alphabetical order for the marks, even for those that are partly illegible (problem that does not exist in the database as there is no order). At the same time the database made it possible to bypass the complicated classification system of the Lugt numbers with it’s a, b, bis and ter numbering system. With this in mind, it had been decided that new marks would receive a continuous number starting from L.3030.

Are collectors still adding their own marks to drawings, and what is best practice if so?

Indeed, we are regularly contacted by collectors who have created their own collector’s mark. As for best practice: ownership marks should be applied with stamps of high quality, for example a metal stamp. The ink should be indelible and stable (non-fading or bleeding) and it should be non-destructive to paper. Ink used by printmakers is suitable (for example Charbonnel, Lefranc, etc.). As for stamping the mark: always first make a test on a piece of paper before applying the mark on the drawing or print. Or ask a paper conservator to do the marking for you! I would also like to repeat what Frits Lugt wrote to collectors asking for advice: choose a discrete design, and apply it - with the same idea of discretion - on the verso!

Do you have a favourite collector’s mark?

If I have to choose, I would say that one of the best symbolic marks ever made by a collector would be the eye by Nathaniel Hone, L.2793.

The Fondation Custodia is built upon Frits Lugt’s personal collection. Are there any drawings in the collection whose marks reveal a hidden story or help to resolve a collection mystery?

There are quite a few drawings in our collection with interesting marks and provenances. One that has intrigued me is the mark of the Earl of Dalhousie: L.717a.

This mark is stamped on drawings coming from two albums. These two albums were acquired by P. and D. Colnaghi & Co. in London in 1922. One album containing drawings by Rembrandt and his School (mostly by Nicolaes Maes) went to Cassirer in Berlin who sold the drawings separately. The other album (almost complete and containing Italian drawings from the 16th and 17th century), was acquired by Frits Lugt. Lugt also sold a large part of these Italian drawings, conserving only a few works, the most important being a drawing attributed to Raphael. Lugt also kept the now empty album itself (it is still in our collection). The album dates probably from the first half of the 18th century, but we do not know by which member of the Dalhousie family it was put together. It is a good example of how collectors’ albums have been treated over time. As selling drawings separately has financially always been more interesting, it is rare to find collector’s albums still intact. Thanks to the collector’s mark on the Dalhousie drawings, it is possible to reconstruct this collection.

Real or Fake

Can we fool you? The term “fake” may be slightly sensationalist when it comes to old drawings. Copying originals and prints has long formed a key part of an artist’s education and with the passing of time the distinction between the two can be innocently mistaken.

One of these watercolours was painted in Scarborough, around 1825, by one of England’s favourite sons as part of a series entitled 'Ports of England'. It is now at Tate Britain, along with thousands of works which were bequeathed to the nation from the artist’s estate after the settlement of his will in 1856. The other work is a copy by an unknown artist. It was possibly painted in London and it is now in the British Museum, where it is listed as a forgery.

Scroll to the end of the newsletter for answers.

Resources and Recommendations

to listen

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the great German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) who achieved fame throughout Europe for the power of his images. These range from his woodcut of a rhinoceros, to his watercolour of a young hare, to his drawing of praying hands and his stunning self-portraits such as that above (albeit here in a later monochrome reproduction) with his distinctive A D monogram. He was expected to follow his father and become a goldsmith, but found his own way to be a great artist, taking public commissions that built his reputation but did not pay, while creating a market for his prints, and he captured the timeless and the new in a world of great change.

to watch

To ready oneself for the upcoming Michelangelo exhibition at the British Museum, take a look back at a lecture given in 2013 by Hugo Chapman, the museum’s Keeper and Curator of Italian and French Drawings from c. 1400 to c. 1800, in celebration of "Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Chapman deftly discusses the various facets, forms and functions of Michelangelo's draughtstsmanship and discuss his relationships with Raphael, the object of his affection, Tommaso de' Cavalieri, and his own students.

to read

Hendrick Goltzius: Painting with Colored Chalk, Alison M. Kettering

A fascinating long read on the development of Hendrick Goltzius, one of the outstanding figures in Dutch art during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, as a colourist. The article examines Goltzius’ portraits of his fellow artists produced in coloured chalks and highlights the interdependence of his subject matter and his choice of medium, as well as the transformative effects of his artistic encounters on a voyage Italy.

answer

The original, of course, is the upper image and it is by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851).

JMW Turner, Scarborough, Tate, D18142; Turner Bequest CCVIII I

Manner/Style of JMW Turner, Scarborough, British Museum, London, inv. no.: 1957,0731.1

A comparable example of a direct copy after a watercolour in the Turner bequest is listed in the British Museum’s digital catalogue with the following entry, which is equally applicable for our chosen example:

“Although the work is kept in a folder labelled 'forgeries' we do not know for certain that it was created with the intention to deceive, as it was possible to copy works by Turner when the Turner Bequest (now at Tate Britain) was held in the National Gallery in the 19th century and in Tate and the British Museum in the 20th.”